Шрифт:

Закладка:

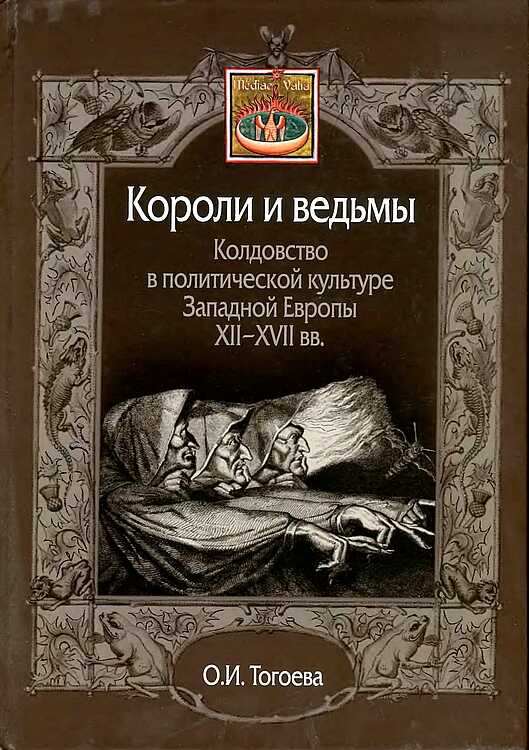

Монография посвящена проблеме конструирования концепта колдовства применительно к политической культуре Западной Европы эпохи Средневековья и раннего Нового времени. В фокусе внимания автора находятся не столько усилия Церкви по сплочению паствы, сколько осознанные демаршы светских властей, использовавших новое явление для создания образа своего собственного врага — врага политического, угрожающего основам государственного устройства, гражданскому миру и социальному порядку. В монографии подробно проанализирована концепция «королевства дьявола» как вполне земного государственного образования, с которым были призваны бороться светские правители; представлена оригинальная «демонологическая» концепция войны — как причины и как следствия засилья ведьм и колдунов; рассмотрены различные национальные особенности охоты на ведьм — прежде всего на территории современной Швейцарии, в Бургундском герцогстве, во Франции и в Англии. Наконец, заключительная часть монографии посвящена проблемам физиогномики и физиологии, позволявших, по мнению европейских демонологов, распознавать ведьм и колдунов и приводить их к суду. Книга адресована историкам, правоведам, филологам, культурологам, а также широкому кругу читателей, интересующихся историей. В оформлении обложки использована гравюра «Три ведьмы» (1863 г.) — иллюстрация к трагедии «Макбет» Уильяма Шекспира.