Шрифт:

Закладка:

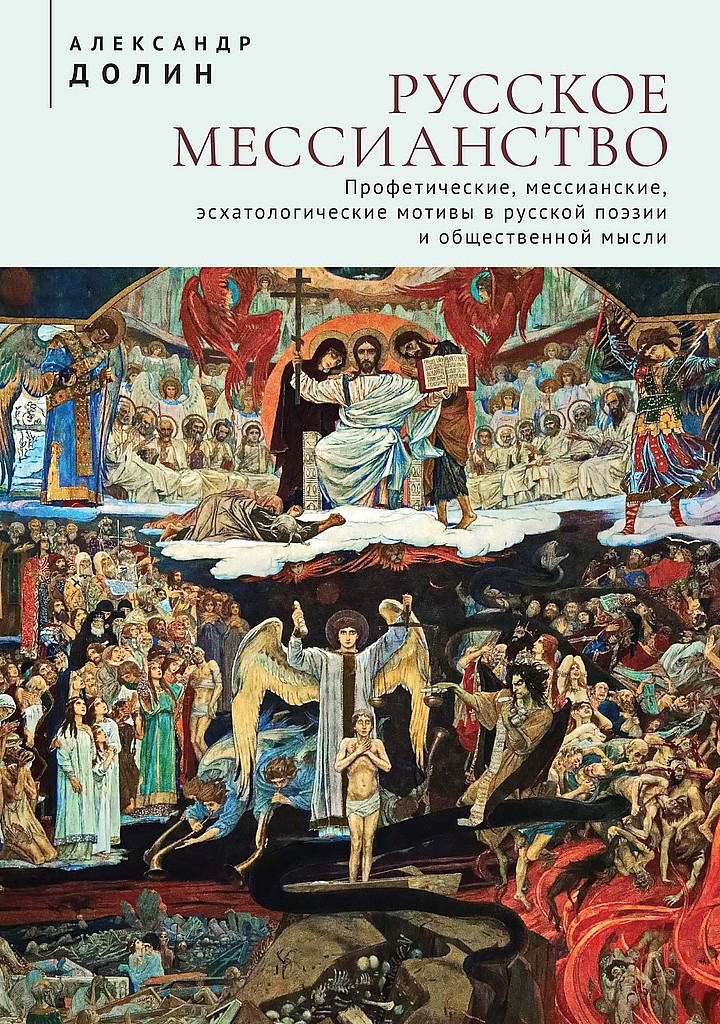

В книге на обширном историческом и литературном материале прослеживается становление и развитие профетической традиции в русской поэзии, общественной мысли, изобразительном искусстве. Пророческие, мессианские и эсхатологические мотивы издавна составляли отличительную особенность отечественной литературы, формируя уникальную национальную ментальность. Апокалиптическая направленность духовных исканий русской интеллигенции XIX — начала XX в. во многом способствовала усилению революционных настроений и осуществлению Октябрьского переворота. В центре внимания автора судьбы крупнейших поэтов, оказавшихся перемещенными из атмосферы культурного ренессанса Серебряного века в советское Зазеркалье и кризис их профетического самосознания. На стыке литературоведения, психологии и культурологии рассматривается роль Поэта в истории и процесс мифотворчества как реальный фактор влияния на социальные и политические изменения в обществе. Для специалистов филологов, студентов гуманитарных вузов и всех любителей русской культуры.