Шрифт:

Закладка:

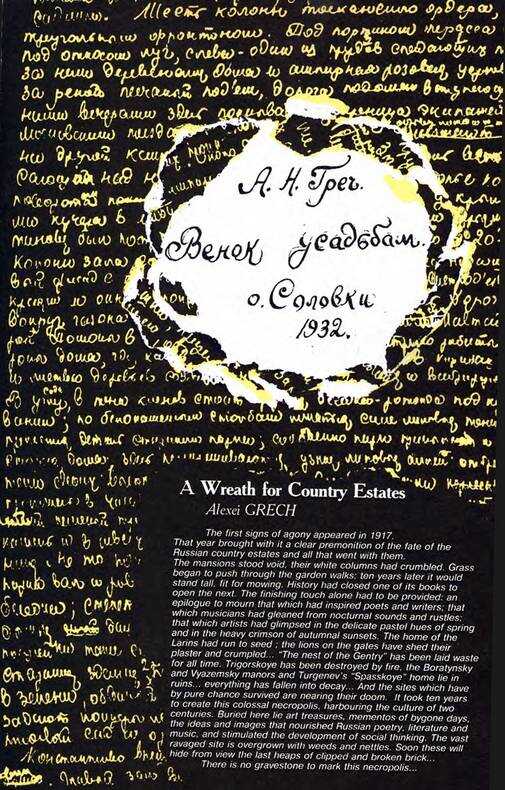

Алексей Николаевич Греч (1899—1938) — москвовед, который посвятил себя изучению подмосковных дворянских усадеб. В начале 1990-х в собрании архивных источников Государственного исторического музея сотрудник А.Афанасьев обнаружил увесистый гроссбух, на котором не было инвентарного номера (то есть формально он как бы в музее и не хранился). Книга содержала рукописный текст — подробное и весьма поэтичное описание 47 подмосковных усадеб и полную горечи констатацию их постепенного уничтожения. На титульном листе значилось: «А.Н. Греч. Венок усадьбам. о.Соловки. 1932». В 1994 году расшифрованная и снабженная комментариями рукопись (к печати ее подготовили историки Л.Писарькова и М.Афанасьева) вышла в альманахе «Памятники Отечества» (№ 32) и стала сенсацией, подхлестнула интерес к изучению послереволюционного краеведения.