Шрифт:

-

+

Закладка:

Сделать

Перейти на страницу:

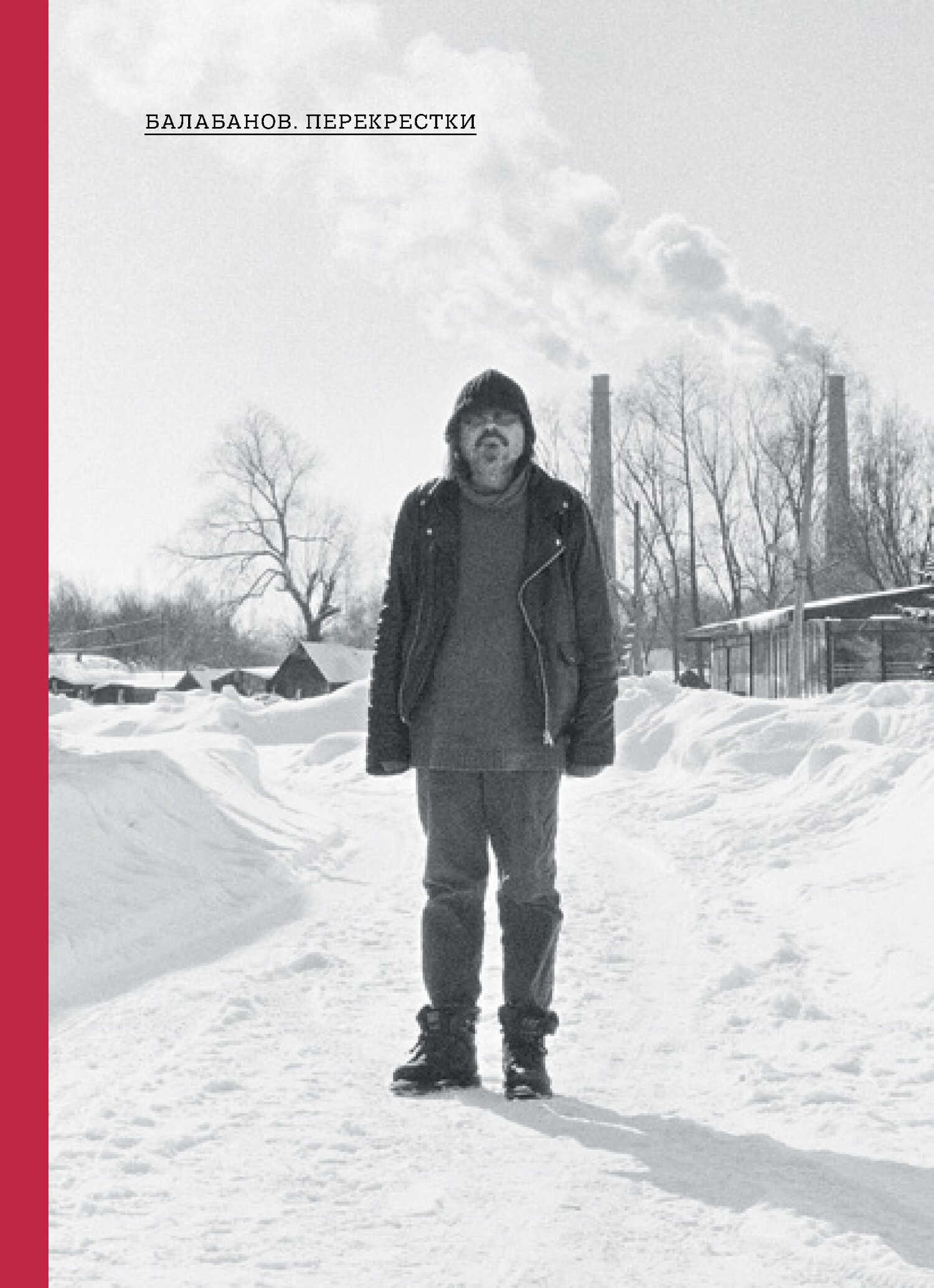

В апреле 2015 года в Санкт-Петербурге и Москве прошли Первые Балабановские чтения, организованные журналом «Сеанс» и кинокомпанией СТВ. В настоящем сборнике публикуются ключевые доклады конференции, в которой принимали участие киноведы и культурологи из России, США и Испании. Среди авторов – Антон Долин, Андрей Плахов, Юрий Сапрыкин и другие исследователи, изучающие феномен Балабанова в социальном, историческом и искусствоведческом контекстах. Сборник дополняют статья Елены Плаховой и фрагменты дневниковых записей Алексея Балабанова, которые были представлены на приуроченной к Чтениям выставке.

Перейти на страницу:

Еще книги автора «Алексей Артамонов»: